Home ATC: Research

Home ATC: Research & Change Management

When I had to decide on the topic on my dissertation, in 2021, the situation regarding the COVID-19 pandemic was still uncertain. After a proper lockdown in spring 2020 there were a few lighter lockdowns with ongoing restrictions including self-isolation. At ANSPs, shifts were designed with remote telephone (sterile) handovers for ATC teams to never meet to prevent spreading the virus (Jaeger, 2021).

Questions

How would we keep the skies open if the restrictions were to get tougher? What if it is not possible to work from the normal workplace (tower or centre) or their backup facilities? Could air traffic services be provided from safe, secluded locations: the air traffic controllers’ homes?

Change Management

Ongoing work-from-home trials for non-operational positions (Jaeger, 2021) have prepared the staff for the new reality, representing the Unfreeze phase of Lewin's Change Management model: Unfreeze, Change, Refreeze in a new shape.

Lewin’s three-step change management model (adapted from Hayes, The theory and practice of change management, 2014, p. 59).

To change the shape of reality, it needs to be unfrozen into a liquid state where change is possible, reshaped and refrozen into the new shape.

The technology is feasible and guidance materials adaptable. CANSO now defines Remote Towers as controlling the airport from any location (CANSO Guidance Material for Remote and Digital Towers, 2021, p. 5). Air traffic data has migrated to the Cloud and can be securely accessed from anywhere in the world (CANSO webinar: Technology Solutions: ATM in a Post-COVID-19 Scenario, 30 June 2020; Indra, 15 January 2021).

The key to change management is to work together with the staff. Rather than trying to make changes TO people, they should be done WITH people and BY people. Rosebeth Moss-Kanter, a professor at Harvard Business School said: “When change is done to people they experience it as violence. When change is done by people they experience it as liberation.” (Cormac Russell, Four Modes of Change, Hindsight 28, winter 2018-2019, p. 10) Staff may resist an imposed change to the point where the whole project may need to be cancelled.

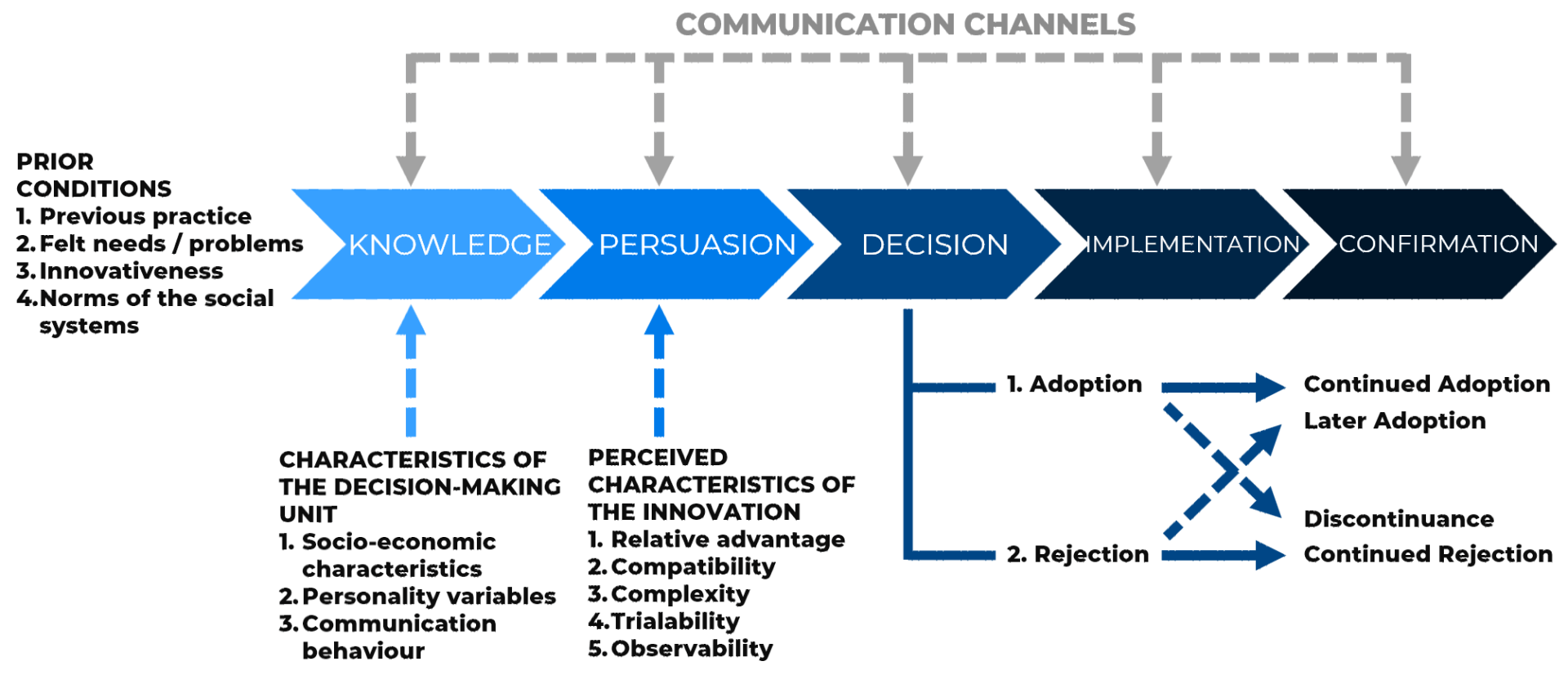

Early stakeholder involvement is key for the concept to be adopted. Not only management, but also staff have to feel a need for change. The innovation-decision process model (below; Rogers, Diffusion of Innovations, 2003, p. 209) lists five adoption stages: Knowledge, Persuasion, Decision, Implementation, Confirmation. However, before the Knowledge stage, there are a number of prerequisites or prior conditions:

- Previous practice,

- Felt needs or problems,

- Innovativeness, and

- Norms of the social systems.

Five stages in the innovation-decision process model. Adapted from Rogers, Diffusion of Innovations, 2003, p. 209.

Sometimes managers, possessing all the

Knowledge

and prerequisites to become convinced (Persuasion) to the innovation, having passed the

Decision

stage, rush to

Implementation

- while their employees are still before the

Knowledge

stage. The staff may

not feel the need for the innovation,

not notice any problems with the status quo, or not have sufficient information about the new way of working.

Additionally, the adoption or rejection decision can change: those who adopted the innovation can reject it later, and those who initially rejected it, can adopt it at a later date. Such changes have been observed in case of remote towers: “even if there is sometimes resistance in the beginning, there are almost always smiling faces when this is operational” (Niclas Gustavsson at 8:04, in: CANSO Academy: improving efficiency through remote and digital towers – Part 1, 2021).

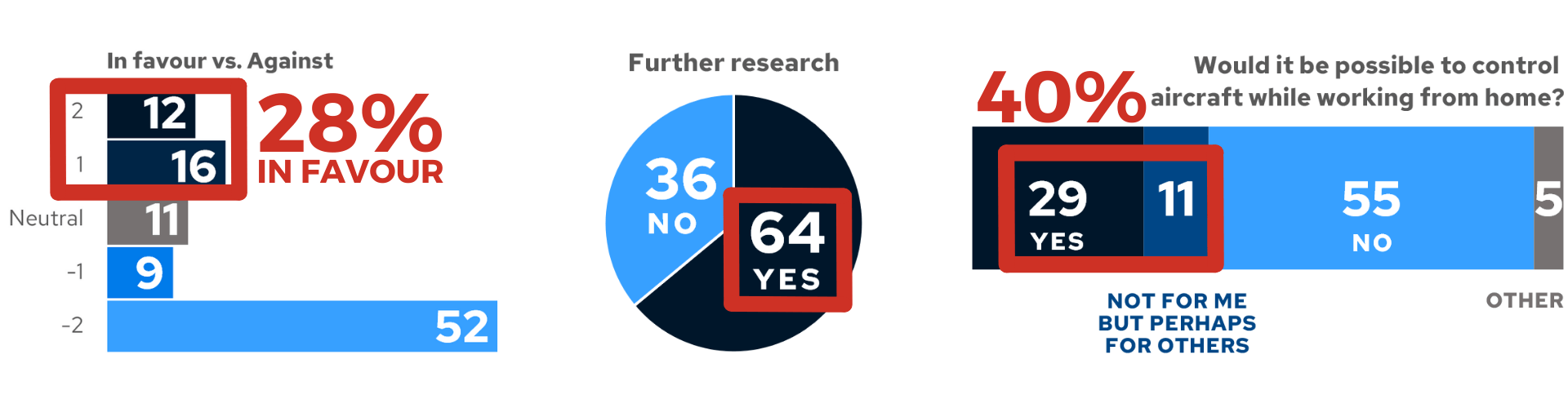

In my dissertation, apart from reviewing evidence for the practical feasibility of the concept of working from home while controlling air traffic, I surveyed 100 air traffic controllers to establish the level of social acceptance of the idea. The results are inconclusive though due to limitations.

Limitations

The research was done via two Facebook groups and Twitter direct messaging and only surveyed those ATCOs who happened to be members of those portals and/or groups, and visited those groups in the days the survey was open (19-22 September 2021). It was not a representative sample of air traffic controllers (estimated at 70,500 globally; Sure Select – Global Air Traffic Control Recruitment and Selection Study, 2014, in: CANSO, ATCO Remuneration and HR Metrics Report, 2015, p. 2). Another study, with access to a different sample of air traffic controllers, could bring different results. An ANSP considering ATC provision from home would need to survey their own employees who may have different opinions.

Social acceptance for working from home controlling aircraft might also differ depending on the country of residence and popularity of working from home in general. E.g. 25% of the Finland population aged between 15 and 64 works from home, while only 1.2% of workers in Bulgaria work from home (McCarthy / Statista, 2021). In my research, the greatest number of respondents from any one country represented the United Kingdom (16) with the next highest number coming from the United States (13), corresponding to 14,000 air traffic controllers working for the Federal Aviation Administration in February 2020; about 1851 at NATS in 2021 (UK; NATS Annual Report, 2021, p. 121) which is the largest of the 62 ANSPs registered in the UK. 44 other countries (not all countries) were represented by 1 to 4 participants.

Demographics

All three air traffic control disciplines (aerodrome, approach and area) were represented almost equally (35%, 37%, 28%). 85 respondents were male and 15 female, which is a similar disproportion to the male to female ratio of 5:1 across air traffic controllers globally (CANSO, ATCO Remuneration and HR Metrics Report, 2015). 47% of respondents had first university degree, 27% completed high school or A-levels, 21% had a Master’s degree, and 5% finished education at GCSE level. Out of 100 participants, 50% (including two women) also had experience in controlling air traffic on a simulation network such as VATSIM, which is done from home.

Results

40% considered it possible to control air traffic from home, with 12 individuals being strongly in favour of the concept (most male with 1 female). Out of the 50 ATCOs with a simulation network experience, 22 considered providing ATC services from home possible (all male).

Despite 55% of respondents considering the concept of controlling air traffic from home to not be possible, 64% expressed their interest in participating in further research in this subject (including 9 out of 16 in the UK). Out of the 37 ATCOs who worked from home before, 17 considered controlling air traffic from home before taking part in this survey, and 20 out of the 43 who experienced remote training.

Amongst the main perceived disadvantages were:

- Human Factors issues (85%),

- cybersecurity issues (80%) and

- not meeting or seeing colleagues (57%).

The main perceived benefits were:

- lack of commuting: saving money, time and environment (65%),

- no need to relocate for work (48%) and

- a greater control over working environment such as light, temperature, ventilation, and eating home-cooked meals on break (41%).

The open-ended responses highlighted teamwork, Single Person Operations, equipment, connectivity, physical and cybersecurity concerns.

Further research

With as many as 64% of respondents willing to take part in further research, and 40% considering controlling air traffic from home to be possible, the topic may be worth exploring further. While it could be technologically possible to control air traffic from home, the concerns identified by ATCOs would need to be addressed together with operational staff engaged “from concept-to-operation to build change consensus and technology acceptance” (CANSO Guidance Material for Remote and Digital Towers, 2021, p. 27).

Although working from home controlling air traffic may not seem to be cost-effective due to the cost of the present infrastructure, this time in history may be an equivalent of the stage when there was “a world market for about five computers” (attributed to Thomas J. Watson of IBM, 1943), or “heavier-than-air flying machines” were “impossible” (Lord Kelvin, the President of the Royal Society of England, 1895; in: NASA, 2003). The Remote Tower concept was first proposed in 1996, and won the first Visionary Projects competition in 2001, when the modern High Definition (HD) video technology was still developing. "Meanwhile, technology changed to HD format as standard, even quad-HD available, and cost for high-resolution cameras decreased from >10 k€ to <5 k€." (M. Schmidt et al, in: Fürstenau, N., (ed.) Virtual and Remote Control Tower, 2016, p. 197).

Standardised consoles and systems, as well as renting or leasing the equipment could help lower the costs, or alternatively the use of a reliable Virtual Reality equipment could eliminate the need of having multiple copies of physical equipment in controllers’ homes; but the primary issue is user interest in the solution.

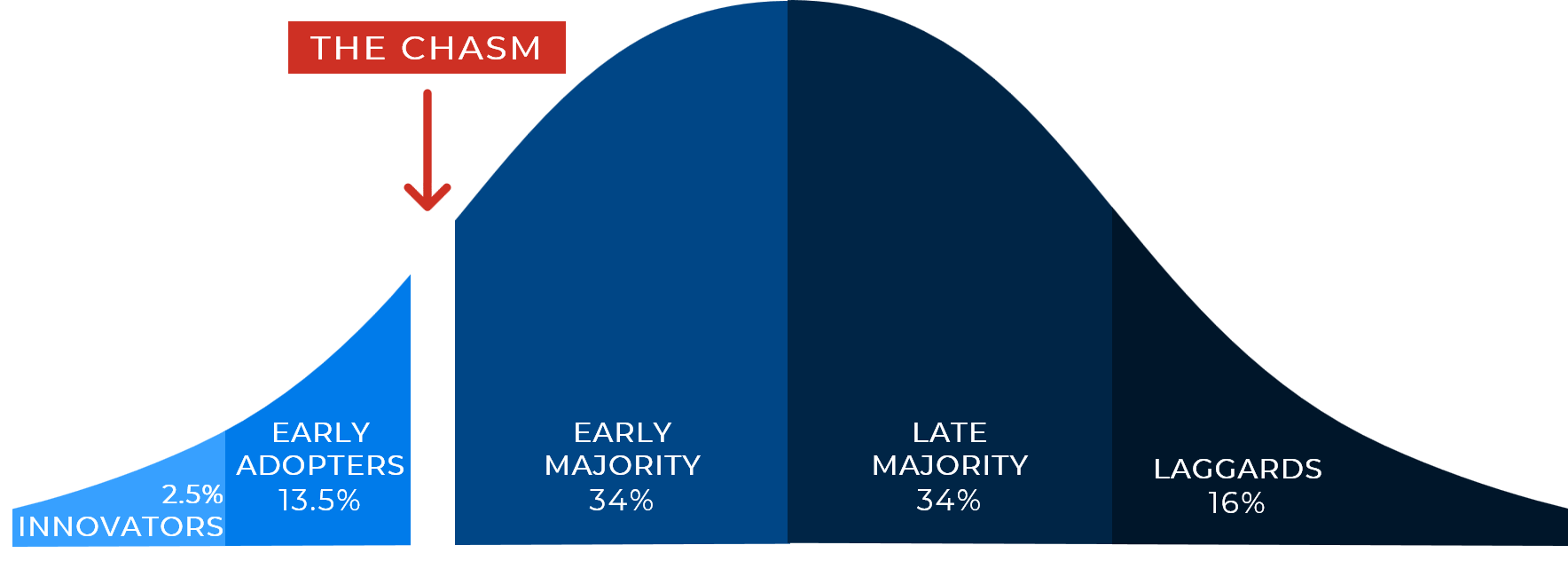

With 40% of respondents considering home ATC to be possible, and 28% being in favour of the idea, this Early Adopters group looks promising. The numbers exceed those in the technology adoption lifecycle model placing a chasm after the first 16%, between the Innovators, Early Adopters (the visionaries or technology enthusiasts) and the Early Majority (the pragmatists). “Every truly innovative high-tech product starts […] with no known market or purpose” and appeals to Early Adopters, while the rest of the population watches trying to find a value in it. Crossing the chasm is considered the most difficult step in the technology adoption lifecycle (Moore, G.A. (2014) Crossing the Chasm, New York: HarperCollins, p. 25-28).

Despite this research being inconclusive due to not using a representative sample, both numbers suggest that this idea may have already crossed the chasm. It may appeal not only to the visionary Early Adopters but also some of the pragmatic Early Majority.

The chasm in the revised technology adoption lifecycle model.

Adapted from E.M. Rogers, Diffusion of Innovations, 2003, p. 318 and G.A. Moore, Crossing the Chasm, 2014, p. 21.

Contingency planning

As an ANSP representative, you may have been wondering what will happen in a stricter lockdown, when you really cannot bring your staff to the workplace, and how you would explain your lack of preparation to the Civil Aviation Authority.

There may be individuals in your ANSP who:

- are willing to control air traffic from home,

- have some home-working experience, and

- have suitable conditions at home.

If you would like to prepare for another pandemic with a strict lockdown or some other disruption and consider your staff working from home, I would be very happy to assist you with further research in the prospect of working from home to control air traffic. Please contact me via the form on the Contact page or via social media.